Projects and management

We need to overhaul our project management. To get there, and to work in the open, let’s start by clearly defining the problem, the fundamental challenges, and our circumstances.

At Open Austin, our projects are for public good and made in the open. Compared to many open source projects that are often for developers, by developers, our projects often involve a more diverse roster of stakeholders like:

- Advocates: people who are passionate about a subject and act as an intermediary between those affected and other (potential) stakeholders

- Designers: people who improve or make new experiences and things through human-centered methods

- Programmers: people who make old machines learn new tricks with high-level markup, low-level assembly, and everything in between

- Researchers: people who focus on understanding and articulating subjects, problems, and ways to achieve a goal

- Subject matter experts (SMEs): people who have a deep or broad knowledge about a subject or specific problem

As a Code for America brigade, we share the common value of civic hacking: working quickly and creatively to help improve government. As a member of that brigade, though, I would like to challenge that a little, in that we ought to help improve governance, not government. That is, we could be slightly more focused on how individuals, things, and societies self-govern or do work themselves toward a public thing (not necessarily government-managed).

How might that shift in organizational focus, and subsequent work, affect government apparatus and how people interact with them? Our stakeholder interaction so far reaches mostly to municipal levels of government and individuals interested in civic work. Perhaps our less conventional processes are not palatable enough yet for more direct intervention in government business, but one important feature of our process is changing how people perceive and interact with public things through hacking.

As a community, we consider any of these stakeholders as civic hackers―quick and creative folks who innovate and push boundaries. However that may not lend well to achieving goals that are more specifically scoped or more wicked. Achieving these goals requires some management to integrate an often variable alliance of people, things, actions, and environments as publics.

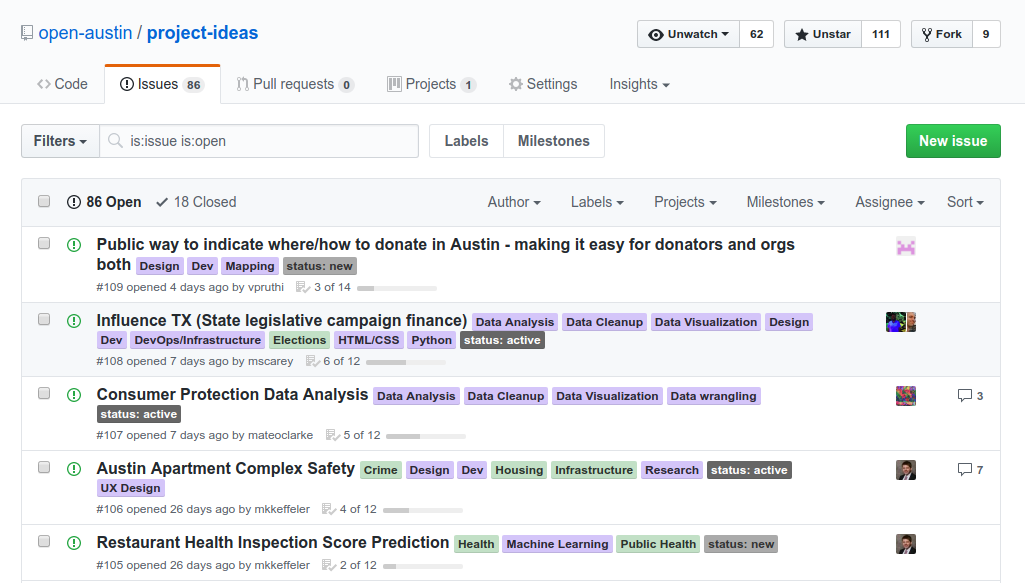

The trouble is many of our projects don’t have project management help, though many have requested it. Without it, those projects could (and have) fall into an unrecoverable state. Whereas one stakeholder might only need to know the particulars of their own work, managing projects requires some degree of knowledge to all work. Fortunately, managing isn’t something only a human can do. We do specialize in technology after all, and project management tech is welcome to take the load off the organization’s leaders.

Notably, across all Code for America and Open Austin materials, all signs point members to tools for project management rather than people. While we have project leads, they are often primarily one of the five aforementioned types of stakeholders rather than a “manager.” Instead, our project management has been developed over the last year based on various frameworks that informed our own Civic Tech Project Planning Canvas.

This canvas is a framework for users to articulate their problem, proposed solution, and logistics required to realize it. Essentially, it helped define the what, who, and how of a project. The problems often come from SMEs and advocates, who may also come to the table with a proposed solution that is then articulated through collaborating with other stakeholders at Open Austin meetings.

Following this initial canvas-building, we suggest teams borrow from the BASEDEF framework to consider how to do work incrementally instead of over-scoping or working privately for so long others forget what they’re doing. This is important considering the asynchronous, remote, and variable work that often loses information from meeting to meeting.

Issues and improvements

Many projects at Open Austin are never completed or delivered to external stakeholders, and many others languish after contributors, champions, or material support are disengaged. This is to be expected from a volunteer group, and it’s actually not too big of a deal when it comes to our values. When I first joined the team, I actually poked people a little too hard to figure out why they hadn’t shared their progress (or any update) with the community.

I toned it down a bit after we discussed what our values were and what we commit, as an organization, to members and friends in the community. However, we would like to have more of an impact on our communities, which requires us to build trust with them, which requires more discipline in how we manage to complete projects.

Early in 2017, after discussing this issue among our leadership team and other Code for America leaders, we put together an agenda to change how we might be more effective at managing our projects and, more fundamentally, our organization itself:

- Define what services we offer as an organization and how

- Develop a project management framework that better articulates expectations with stakeholders and builds trust

- Research legal structures required to accept more impactful work

- Pilot our nonprofit capabilities with a highly impactful project

- Pilot our nonprofit organization with a government project

Services and values

Our leadership team met to first tackle our problem of value definition: what should we offer, and how do we create value of that to others? We first reconsidered how the leadership team itself is organized as a community-driven entity. This helped us to more quickly and effectively analyze and implement improvements to our core processes that would help us identify issues with projects and enable their leads to resolve them with or without our help.

We then iterated on our organization values, aligning on our dedication to community-driven policy setting and idea generation, both in terms of what we will and won’t do. The results of these policies and ideas would then be scoped to projects we can accomplish, which then begs the question of management. Following from our civic hacking ethos, our form of management is born from our collective values and cultural organization rather than the political or mechanical organizations of governments and corporations that we also participate in.

To better understand this, we researched how similar organizations managed projects so that we could design and test our own process, including the following:

- Open Oakland’s “Leading a Project”

- Smart Chicago’s “Collaborative Project Management”

- Code for America’s “Civic Tech Patterns”

- U.S. Digital Service’s “Playbook”

- U.K. Government Design Service’s “Design Principles”

Without our own process, we were not fully realizing our capabilities and opportunities, affecting our mission to quickly and creatively innovate civic services.

Our project management framework

In addition to seeking out peer organizations’ management techniques, we also conducted a more academic literature review. From research by Lakemond et al. and Wake and Bogers we found an interesting parallel between their open innovation practices in enterprise and our civic innovation in a volunteer organization. In particular they found that project management is quickly supplanted in importance by knowledge matching.

Lakemond et al. found that project management had a strong impact on performance in the early stages of a project, such as collaborating during ideation. It was especially important when there were many different stakeholders and contributors, but less so for later stages of a project’s completion. Rather, at these late stages “knowledge matching” may have been more important than project management.

Knowledge matching in our case could mean sharing Open Austin’s and our partners’ technological competencies and knowledge resources. That might be in the form of workshops, consultations, or training. The function of it though is bidirectional learning and collaboration, which could determine performance on a project at all stages. It may be more determinant, though, at later stages as project management becomes less effective, as Lakemond et al. suggested. For the early stages of projects, including finding problems and ideating around them, we could borrow the expertise of companies that employ people dedicated to project management.

Wake and Bogers described how companies often seek external sources to help them innovate in the open, including some who turn to the crowd or intermediaries. An example of both are members of Open Austin and other Code for America brigades, as we are a large and diverse group of people who do both technical and social work. And we regularly work together, often at hack nights, hackathons, and other types of innovation jams to offer this environment to entities in the civic tech space. However, companies often don’t just hop right into this sort of hack environment. They often require an intermediary to guide them and operate in new environments like these.

By providing that environmental savviness along with the requisite subject and technical knowledge, we can trade for their project management skills in a project’s early stage, allowing us to at least structure it through some scheduled completion. While this might not be as “complete” as we may expect, it is a step toward that. We and other brigades already do engage companies like this to some degree, but we don’t earn as much in long-term commitment. For example, many companies participate in ATX Hack for Change, but we don’t get quite the same result from that as we do with our community partners like Austin Tech Alliance.

We can do better in the former space by making clear requests for time, artifacts, and communication before we break from jam environments. Increasing engagement in general with those management-savvy hackathon-curious companies may also improve their chances at participating individually as a member or visitor, as well as future organization-level work. This is something to be explored, and presently, companies may not yet be incentivized adequately to work with us on an organizational level. Some outright refuse unless we are legally organized in particular ways.

All things considered, we can better ensure our projects reach some measure of completion by organizing projects for knowledge matching with external stakeholders. Project management could use more structure in early stages to help organize, while as the project progresses we supplant that structured management with a bespoke knowledge commons. We would need to describe that commons policy on an abstract level, involving project governance and knowledge sharing.

Our first step in this direction has been a presentation to our members at a civic tech night. In this, I described how we have managed projects so far and some skills and techniques I learned from Mozilla’s Open Leadership Training. From there, we developed a guide and checklist for sharing project ideas, both for the first time and for progress as the project develops. I also set policies and checkpoints for the projects lead position to best facilitate and, if necessary, intervene in a project’s management to fully realize its potential.

Legal structure

We do impactful work. We engage with multiple communities year-round, culminating in ATX Hack for Change, and we engage with companies through partnerships like Austin Tech Alliance and CityUp. We also interact with more loosely organized groups like Data for Democracy and other meetups.

However, more structured entities like businesses, nonprofits, and government may present opportunities that a civic-conscious hacker may not have the visibility and resources for. Those entities, though, often require some legal assurance we’re not going to run off with their money, make them look bad, or come off as unprofessional.

To make this happen, we need to organize Open Austin more formally, particularly as a 501c3 nonprofit corporation.

For about four months we gathered our core values and practices into a bylaws document. Using this, we are now in the process of submitting our paperwork to formally incorporate. As a 501c3, we would be able to do business and participate in other nonprofit programs from corporations and government that require incorporation. We also join a network of other Code For America brigades that have incorporated to share management experience. The process has also been a test for our values, both in the decision to incorporate and how to incorporate our membership.

Keep in mind that “the corporation” is the entity that owns assets, manages work on behalf of the whole organization, and directs group activities. Practically speaking, it is both inclusive of, but distinct from, what would be called “Open Austin” as has existed as a group of friends, a Meetup group, a civic hacking organization, etc.

Considering our previous issues with helping Open Austin members, including project leads, manage projects and facilitate their other efforts, we had some trouble deciding whether to include members who weren’t on the leadership team in the corporation. While members would of course intrinsically comprise Open Austin forever, the corporation does not include members other than the board of directors (also known as the “leadership team” or “core team”). Indeed, even our current practices on the leadership team haven’t required oversight by the general membership.

Still, there is much to test from here. The incorporation itself takes some months, and we likely wouldn’t take on any major projects in the interim. For example, we also need to consider that major risks come with major opportunities. As such, we are currently working on ways to set indemnification policy such that, if we are sued for unintended or fringe effects of one of our projects, what are our legal and fiscal options? Similarly, if a private or public organization that does not sit well with us asks us to work on a project, how much should our organizational values affect the decision?

Piloting the nonprofit model

One successful project from Open Austin is Budget Party, a gamified experience that helps people understand and augment a city budget for Austin. As a pilot for our new organization, how can we test our values, project management, and new organizational structure by working on this?

Having demonstrated we can operate normally as a nonprofit, and also having discovered new ways we can do civic work, we can then try directly influencing our city government itself. How can we break into this space, how might we change Open Austin in the experience, and what will we find about how government might turn to hacking as a way to improve life for Austinites?

These are open questions that I’d like to leave as an exercise for the reader. Consider it a prompt that anyone may contribute to (i.e. we will retweet you or even host your post).

What do you think?

Hopefully having this article around will help other organizations, like other Code for America brigades, organize themselves in a way that innovates how civic hacking communities effectively innovate and collaborate. Let us know if it did or even if this doesn’t sound right at all.

What are your stories of organizing a volunteer group, managing open source projects, and incorporating a nonprofit? We’re always curious and always open. Respond and join the discussion on our Slack team!